by Brendan Kimbrough | Mar 11, 2025 | Honduras, SAMS Missionaries

by Susan Park, SAMS Associate Missisonary

Our plane leaving Pittsburgh was delayed about half and hour while they de-iced it. When we arrived in San Pedro Sula it was 90º! Talk about extremes!

So much has changed since we lived there. We discovered that now to fill out the customs form, you have to do it with a QR code on your phone. (Cell phones are everywhere now.) We walked right past the posters so the fellow who was helping us, did it with his phone for us. When all eight suitcases and backpacks went through their x-ray machine, they pulled aside the big black one. “What is this?” “It’s a donated used sewing machine. It’s going to a workshop for poor women in the capital to learn a trade. And there’s another one in that suitcase.” And I handed him the letters from the workshops explaining that they were all donations. I was praying that he didn’t want to open the machine case itself as it was stuffed full of thread in all the spare spaces, which would have spilled all over the place. Praise God, they didn’t open any of the others and let us go without having to pay any duty on what we brought in.

Not having gone to bed the night before because the shuttle picked us up at 3 AM, we took naps until dinner time. Bp. Lloyd Allen met us and we got caught up on what has been happening in the diocese and the plans for the workshop that John and he would be teaching with the new deacons and those who are pursuing the permanent diaconate.

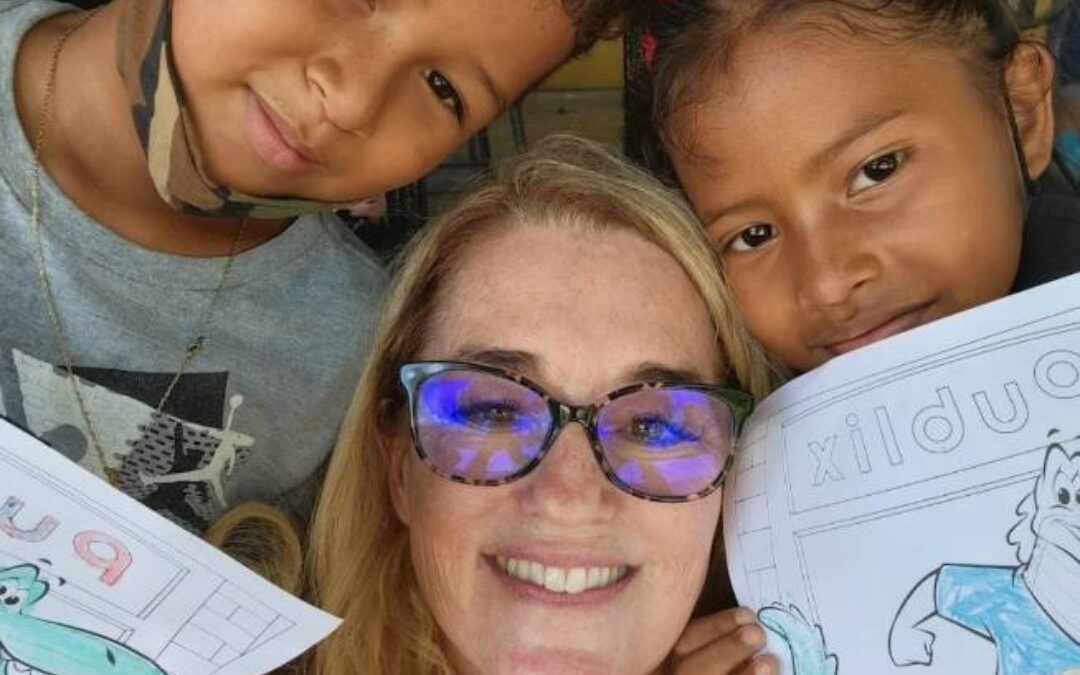

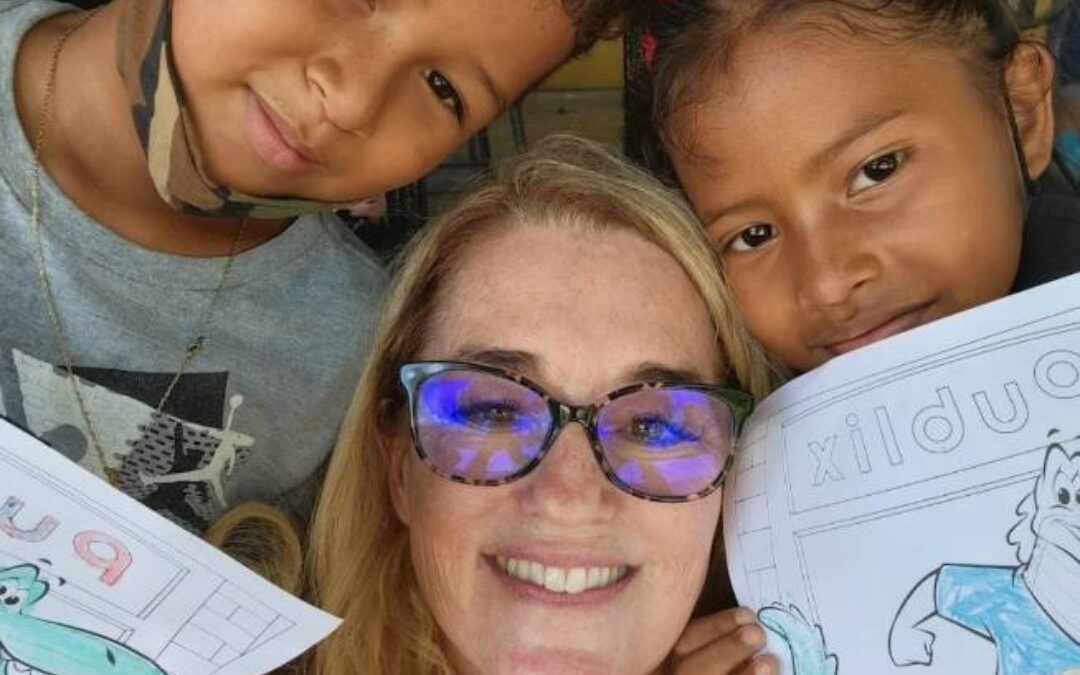

Up at 6 the next morning to head to Tegucigalpa the capital where I would see the workshops and drop off the machines and supplies. Bishop Lloyd sent me in a church van with a driver to help with the two suitcases, a sewing machine, and my backpack so that I didn’t have take a bus. About 6 hours later, after trying to follow GPS and getting vaguely lost, we arrived at the Jericho workshop and school where we dropped off the first machine and met Noah (son of former SAMS Missionary Betsy Hake) who introduced us to the women in charge of the workshop. We unpacked the very full, very heavy suitcase with the sewing machine and materials. Noah showed me around the school as well and introduced me to some children from an outreach project they have. Unfortunately, I was not able to meet with Betsy as she was away on a much-needed sabbatical. The Jericho Villa where Betsy lives and has the children’s home and another school is several hours further away out in the countryside, so I was not able to go there. The far photo has some of the items that are for sale made in their workshop.

Then onto LAMB Institute where I would stay with SAMS missionaries, Steve & Debbie Buckner. LAMB was founded almost 25 years ago by former SAMS Missionary Suzy McCall as the Latin American Mission and Bible School to train Hondurans in discipleship and as missionaries. Now the program focuses on children who have been abandoned. The youngest is only 6 months old. When they turn 18, the government regulations state they must move out, so they have established a transition house where they live and help them finish schooling to be able to get a job. Their recent project is a home for those who will not be able to live on their own; 2 children who are blind, 2 with cerebral palsy, and 4 others with mental health and behavioral issues. They also have a school on the campus and another in the village down the road. They have a farm where they raise a lot of their own food, as well as chickens and sheep.

This is Alexi, who was my driver, with the sheep eating sugar cane

The other man with the chickens is Ariel who works the farm.

The children are encouraged to help as well.

Debby unpacking the supplies

Debby was delighted to get the sewing machine and supplies as she teaches all kinds of handcrafts with the girls. You can see the pile of fabric as well as the supplies in the suitcase. It was stuffed full as was the sewing machine case. Steve teaches wood working, helping them learn about tools and how to use them. They have a store that’s in an old school bus. When the crafts are sold, a tithe goes to the church and some money goes to cover the use of the tools or the supplies and some money goes into a savings account for the children which is theirs when they turn 18.

Crosses that the girls made with “diamond dots”

Steve, Debby and me.

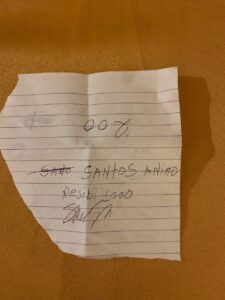

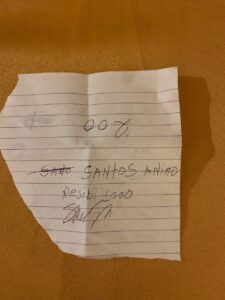

As is often the case, there was a misunderstanding. Alexi, my driver, didn’t have family there to stay with. Praise God, Steve knew of a hotel they had used for groups that was close by their house. But it took only cash, so we went in search of an ATM 20 minutes away. The first one kept rejecting my cards, only to find that it was broken. The fellow outside the Municipal building told us where to find another one, which thankfully was just down the road. Success! Back to the hotel to pay for the room, only to find that the owner wasn’t there, only a security guard who didn’t have change for L/.500 bills. So I gave him most of the money, gave more to Alexi and told him to go buy breakfast in the morning so we could break the bill and pay the rest that we owed. Well, Alexi was the only one staying there and the guard wanted to go home, so he just gave Alexi the key to the gate so he could come back in after he left for dinner.

This was a receipt for the money I gave him; a corner torn out of a book.

Saturday morning, Steve took us around and showed us the children, the farm, and the buildings. It is amazing what God has done in such a short period of time. Then we took off back to San Pedro Sula, another 6 hour ride. I was glad to get back to the hotel and rest.

Thank you all for your prayers. The next letter will cover what John is doing.

To learn more about John and Susan Park and their ministry please visit this page.

by Brendan Kimbrough | Feb 28, 2025 | Refugee Ministry, SAMS Missionaries, Uganda

It’s a dusty, jaw-rattling, two-hour drive over rough Ugandan roads to get to the Kiryandongo Refugee Camp in northern Uganda. SAMS Missionary Cathy Clevenger and her team make the drive once or twice a month to minister to groups of refugees living there, but wisely, not during the weekly food distribution. The camp is a city in its own right. A sprawling sea of homes spread out for miles, which include schools, churches, make-shift shops, U.N. health clinics, and the requisite food distribution points. It’s comprised of nearly 100,000 people, who represent just a portion of the fallout in terms of the real human cost caused by the carnage of civil war and continuing tribal conflict in South Sudan and Sudan.

One of the stark realities, besides the sheer size of the humanitarian dilemma here, is the excruciating trauma. “The majority of the population in the camp is women and children” says Cathy. “Most of the Sudanese men have either been killed or remained behind in their tribal areas to fight. The stories are real, yet always heartbreaking. So much violence, displacement, killing, and loss of loved ones has taken place.”

It could be overwhelming to confront such a human tragedy, but Cathy’s well-trained team faces it head-on in the hope and the power of the Gospel. Cathy draws on decades of experience treating trauma as a licensed social worker in the U.S. before the Lord called her to East Africa. In her current role as Counseling Coordinator for the Diocese of Masindi-Kitara, Cathy had been treating Ugandan teenagers at a local remand home for incarcerated young boys awaiting court dates. Cathy still carries out that important work, while ministering to the burgeoning refugee population and their dilemma that God had placed in front of her in late 2023.

With the scale of suffering that exists at the Kiryandongo Camp, one question arises: How can this many people possibly be treated who have experienced such terrible things? Much of the answer lies in the power of the Gospel, not only to open up people to understand their own response to trauma and begin to heal, but then to also trust that those same people will take what they’ve learned to others. It’s a replicative model of treatment that by God’s grace makes use of Scripture, small groups and guided teaching.

Cathy and her team typically speak to an assembled group from churches within the camp about trauma and teach them what trauma looks like, what the responses to it typically are, and why people respond the way they do. They use the story of Elijah and the dramatic showdown on Mount Carmel where Elijah successfully demonstrates the power of God over Baal, which prompts Queen Jezebel to threaten to kill him, creating intense fear and a desperate flight for his life (one of the four main responses to trauma). God intervenes with the appearance of an angel who provides for him. Elijah reaches Horeb where he encounters the still small voice of God which reassures him of his purpose and gives him new instructions.

Cathy and her team typically speak to an assembled group from churches within the camp about trauma and teach them what trauma looks like, what the responses to it typically are, and why people respond the way they do. They use the story of Elijah and the dramatic showdown on Mount Carmel where Elijah successfully demonstrates the power of God over Baal, which prompts Queen Jezebel to threaten to kill him, creating intense fear and a desperate flight for his life (one of the four main responses to trauma). God intervenes with the appearance of an angel who provides for him. Elijah reaches Horeb where he encounters the still small voice of God which reassures him of his purpose and gives him new instructions.

Not only does the story reveal the vulnerability of God’s own prophet, but it shows the reality of living as a Christian; that strong belief can be severely tested by acute suffering, and that turning to God for renewal again and again is vital, especially in times of crisis. The teaching is designed to show camp participants how they can also use this teaching with others within the camp. This ‘teaching plus training’ approach is designed so that the refugees can use it within their own churches inside the camp as they recognize those who have symptoms of trauma. After the group teaching, small group work is done where one-on-one therapy is held.

Cathy says, “We offer hope and we see real deliverance from the loss of it. We don’t have food, or clothes, or other assistance to give them. We offer something far better. We offer them Jesus, his healing, and his transforming love. The Gospel promise of real and lasting restoration through healing is at work here among a people who have lost everything.”

by Brendan Kimbrough | Feb 28, 2025 | Short-term Missions

Jennifer Ruben is a Jesus-follower and an Anglican committed to help other Anglicans engage in mission. As the founder of One 8 Go Global, her main aim is to summon others to take the Gospel to all nations. Her ministry takes its name from Acts 1:8, “But you shall receive power when the Holy Spirit has come upon you; and you shall be witnesses to Me in Jerusalem, and in all Judea and Samaria, and to the end of the earth.”

Throughout its history, SAMS has invited churches to enhance their global outreach through short-term missions that contribute to the long-term ministry of missionaries and the global Anglican church. SAMS is now promoting one more way for both churches and individuals to participate in a short-term mission by commending One 8 Go Global. This option will provide teams and individuals with a complete package, starting with preparation and concluding

with debriefing!

Leading short-term missions takes experience, training, logistical and spiritual support on the field, and global partners. Jennifer has fostered relationships in Latin America, Africa, Asia, Europe, and the USA with several different denominations. In 2025, One 8 Go Global is planning

six missions. Jennifer will completely prepare the team, accompany the team, and debrief the team. She is currently working to fill-out the Malawi team in July, who will conduct village evangelism, discipleship, food relief, and a children’s program. Email Nita at info@sams-usa.org to connect directly with One 8 Go Global.

by Brendan Kimbrough | Feb 21, 2025 | Europe, SAMS Missionaries

New SAMS Missionary Candidates Lee and Ela Nelson are responding to a call to contribute to the re-evangelization of Europe through the Knüll Camp and Conference Center in Schwarzenborn, Germany. Two ACNA jurisdictions will come alongside Lee and Ela and their children for a collaborative sending effort. Both the Reformed Episcopal Church (REC) Board of Foreign Missions and the Diocese of the Fort Worth are engaged in directly supporting and encouraging others to join this ministry as Senders of the Nelson family.

For five decades REC Bishop Gerhard Meyer with his wife Grace led the Camp, where many have been blessed in the Lord. As the new director, Lee will be developing a training center to encourage the planting of healthy, multiplying churches throughout Europe.

While work needs to be done to upgrade the camp, Lee and Ela envision it as a strategic place to launch initiatives like the training center. A second focus will be to make the camp a hospitable refuge for beleaguered Christians, lay and clergy alike. Please pray for the Nelson family as they seek Senders and then transition

from Texas to Germany to equip and refresh the church.

Visit the Nelson’s page

by Brendan Kimbrough | Jan 17, 2025 | Netherlands, Netherlands

We see the Light of the World…

… in Christ’s work all around us. Here in Amsterdam at this time of year beautiful lights are on display all over the city reflected in the many canals and creatively adorning the historic buildings. But we live in a tumultuous time and sometimes the lights might give the impression that all is well, but darkness is all around.

Ukrainian refugees continue their sojourn here and war is near. No Amsterdammer can forget that thousands of Jewish residents were sent away to perish in the Holocaust. The streets glittering with Christmas lights also display small brass commemorative plates on the pavement in front of homes where Jewish families once lived. Hatred of Jewish people cropped up recently. Rioting hooligans after a football (soccer) match remind us that human sinfulness remains. One of the leading Rabbis in Amsterdam recently stated that both Jewish and Muslim communities presently feel themselves scorned and unwanted, for it is all too easy to blame the nearest immigrant or person who is “not like us.” The darkness lingers.

As a church in the heart of the city we continue to meet curious neighbors and visitors who are interested in things spiritual or something they just cannot quantify. Is it the light of Christ they see? Often they are surprised by our diversity with so many nationalities, ages, economic backgrounds and professions. We trust that it has to do with the music of Messiah reverberating from the lives of our people and the warm hospitality driven by love, leaving an unforgettable impact as the light of Christ shines through. Here are a few recent examples.

- “Ned,” a 74 year-old, got the difficult news of terminal lung cancer. Though he lived only 3 more weeks, he was amazed and comforted as God’s people rallied around. He said, “I’ve never had so many people around me in all my life!”

- Life-long church member, “Phylis,” is 95 and lives alone in an assisted living home. She looks forward to singing Christmas carols and offering hospitality to our pastoral team when they visit. Her trust in the Lord in old age is such an encouragement to many.

- “Alice” is a 16 year-old who recently began attending youth group with a friend. She eagerly participated in our recent carol service as a reader.

- Jono, another teen, saw the light of Christ in the lives of both of his grandmothers. Through their prayers and encouragement, he began faithfully attending our services.

- “R” has experienced life on the street for the past two decades due to issues of mental illness. It is gratifying that our people welcome him to our services. Just this week he attended a midweek communion service on a blustery day. He was in tears as we took bread and cup together in anticipation of that day when we will reside in that city “where the Lamb is the light.”

“The light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it.” John 1.5

Cathy and her team typically speak to an assembled group from churches within the camp about trauma and teach them what trauma looks like, what the responses to it typically are, and why people respond the way they do. They use the story of Elijah and the dramatic showdown on Mount Carmel where Elijah successfully demonstrates the power of God over Baal, which prompts Queen Jezebel to threaten to kill him, creating intense fear and a desperate flight for his life (one of the four main responses to trauma). God intervenes with the appearance of an angel who provides for him. Elijah reaches Horeb where he encounters the still small voice of God which reassures him of his purpose and gives him new instructions.

Cathy and her team typically speak to an assembled group from churches within the camp about trauma and teach them what trauma looks like, what the responses to it typically are, and why people respond the way they do. They use the story of Elijah and the dramatic showdown on Mount Carmel where Elijah successfully demonstrates the power of God over Baal, which prompts Queen Jezebel to threaten to kill him, creating intense fear and a desperate flight for his life (one of the four main responses to trauma). God intervenes with the appearance of an angel who provides for him. Elijah reaches Horeb where he encounters the still small voice of God which reassures him of his purpose and gives him new instructions.